The potential of the personal mindset as a driver of innovation

If we want to promote the harmonisation of employers’ and employees’ interests in digital transformation, it’s the mindset and thus the level of maturity that really matters. The chances of harmonisation succeeding depend on how broad the horizons of the stakeholders are and how they construct their inner conception of the world. This worldview changes as we grow older, and how this happens has been the subject of much research. This research has come up with some interesting findings, which we have used to develop a model that reveals the mindsets management and employees are acting from.

The model uncovers the development potential of both individual employees as well as the company. If leaders can evolve to cope with the demands of emotional leadership, they will have no trouble managing employees with vastly different mindsets and be able master radical change and new challenges. The company will becomes a powerful force for innovation and thus attract more “high potentials”.

Values such as sustainability, employee orientation, fairness and open mindedness, which many companies hold dear, can thus be effectively put into practice on a daily basis.

We all know what it’s like when you work in a company and think to yourself, “They’re really strange”, “Somehow this is just not my world”, “I really don’t want to work like them”. Things that seem important and meaningful to others might seem ridiculous or totally uninteresting to you. It’s highly likely the reason for this is that your mindset is out of sync with the company’s. Our attitudes and our mindset are determined by the ways in which we construct our conception of the world. How our construction of reality changes as we mature has been explored by a number of developmental psychologists including Jean Piaget, Abraham Maslow, Ken Wilber, Jane Loevinger and Clare Graves.

They reached two new conclusions: development does not cease when a certain age has been reached, and cultures develop in a similar way – as the collective image of our inner maturity. Calling for harmonisation of attitudes and values doesn’t mean that everybody has to inhabit the same mindset. However, it makes sense to put people in leadership positions who have a high level of maturity and can assume a spectrum of mindsets. They have what is needed for two essential tasks of leadership:

- Recognising the mindset of employees and handling them so that they can make an optimal contribution to the bigger picture, regardless of whether they follow orders or organise their work themselves.

- Supporting employees who wish to develop their skills and abilities.

Ultimately, to attract the right talent, companies should make sure that they give employees with different mindsets space for opportunity.

1. The development of mindsets

This biographical series of mindsets and levels of maturity can be described as follows:

The self-orientated-impulsive mindset

We go through this stage of learning in our development from around between two to five. In the self-orientated impulsive mindset we are deeply caught up with ourselves and our own needs. Reflective thinking and a sense of longer periods of time are not yet possible in this mindset. We reject feedback and remain stuck in stereotypical ways of thinking that concentrate more on the concrete than the abstract. Other people are a means to an end and our behaviour is largely opportunistic.

We are not yet able to grasp or control our own emotional experience. We lack the ability to empathise with people. Our ways of thinking are simplistic, it‘s always somebody else’s fault and somebody else always started it. We tend to be defensive because we lack a sense of security and genuine self-awareness.

The group-centric-conformist mindset

We learn this mindset from the time when we first begin to speak consciously of the “we”. It’s a mindset that accompanies us through primary school. In the group-centric conformist mindset we learn the rules and norms that govern our social environment. Our identity is strongly defined through belonging to an “us” rather than through our own individuality. Obedience and submission are predominant in this mindset. This is associated with strong feelings of guilt if we fail to comply with conventional norms. We have a desire not to lose face, which allows us to avoid conflict. We prefer to steer clear of conflicts and keep our mouths shut. Our own feelings and inner life are still intangible. We accept criticism if it’s based on principles that are set externally: “But the teacher said that …”

The rationalistic-functional mindset

The rationalist functional mindset is the next stage of competence-building and the beginning of what psychologists call the ego. Nascent self-awareness allows us to take a more nuanced view of ourselves. We can now see a variety of perspectives and we become less judgmental. The desire to have our own opinions is born and the wish to delineate ourselves from others. We develop our own views about what is right and wrong. In doing so we turn to clear standards for orientation. We exercise ourselves in rational thought in which causal explanations are written big. We’re not interested in lengthy debates. We tend to value efficiency more than effectiveness. We still see ourselves as driven by external exigencies within which we believe we must function. In our own development we usually go through this mindset at the onset of puberty.

The self-determining-confident mindset

In the self-determining-confident mindset we acquire our own values and ideas. These personal benchmarks guide us through life. We develop a strong goal orientation and are driven by the desire for self-optimisation. A much richer and diverse inner life unfolds, which accepts the complexity of situations and respects individual differences. In this mindset we stand confident in life and decide what kind of relationship we will embark on with what kind of person. We are often oblivious to our own blind spots or our own subjectivity. The “ego” is greatest in this mindset. It corresponds to that of a late teenager who knows a lot and is competent, but whose capacity for empathy has not yet fully developed.

The relativistic-individualistic mindset

The relativistic-individualistic mindset makes us aware how our own perceptions shape our view of the world. We begin to put things into perspective and question our own and others’ points of view. Such a competence enhances our ability to empathise and we now recognise contradictions in ourselves and the outside world that we had previously tended to dismiss out of ignorance or cynicism. We see that everyone is shaped by their own fundamental qualities, culture and life history. And we learn to take account of this when communicating. In this mindset we are much more aware of our emotional inner life which we now discover as an important supplementary resource for shaping our views. The rich plurality of new facets and nuances this gives us makes us more individualistic and authentic.

The systemic-autonomous mindset

In the systemic-autonomous mindset our competencies expand to include the ability to take a fully-fledged multi-perspective view and we learn how to take a systemic view of relationships. Recognition of circular connections enables us to integrate contradictory opinions and aspects. In this mindset we are ready for creative ways of tackling conflict and we can also deal with ambiguity. We respect the individuality and autonomy of our interlocutor and are prepared to accept full responsibility for ourselves, our thinking, feeling and acting. This leads to higher motivation for self-development and an even stronger awareness of our inner subjective interpretive patterns. We can see our thoughts and feelings as subjective and by doing so we have a much larger number of cooperative options for action. An awareness structure becomes manifest or an understanding that we are permanently constructing ourselves and the world anew.

2. Exploring your own understanding of leadership

Do a little experiment and complete the following sentence stems. It’s even better when you give them to various colleagues and then compare the results.

- The job of a leader is to …

- What I like about being a leader is …

- What troubles me is …

- When colleagues are helpless, …

- Success is …

- Rules are …

- My main problem as a leader is …

- When I reach my limits, …

- Leading others, …

- When I exercise power over others, …

- When I’m criticised, …

- My conscience bothers me when …

Complete the sentences any way you like. There are no right or wrong answers. You can be as profound and complex as you like.

Here you can find a set of sample answers that will help you with classification and analysis. Each of the completed sentences reveals which mindset we are using and have internalised. The vast majority of problems arise when we communicate with one another from quite different mindsets and thus from quite different views of the world. We’re often not aware of this because each of us thinks that their subjective view is the “correct” one.

The ways in which we complete the sentences illustrates our understanding of leadership, making it transparent and opening it up for discussion.

It’s a good idea to do this exercise in self-reflection together with a group of leaders. It’s important that everybody notes that there is no right or wrong mindset. The whole point of the exercise is to recognise which mindset is being displayed and then to decide how to effectively leverage it so that it may contribute to the overall result. One of the frequent outcomes of this process is that leaders often express a wish for further personal development (see diagram on page 96).

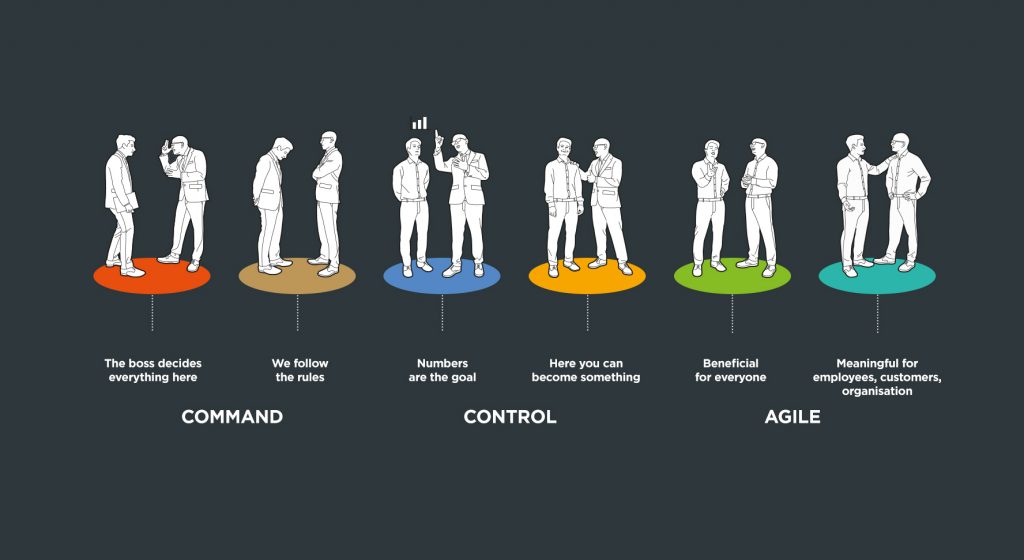

3. Management’s mindset determines the form of the organisation

We find it easier or more difficult to change our mindset according to how old we are and how developed our personality is. A mindset is not static. We often change it according to the situation we find ourselves in. However, we often do have a biographically conditioned tendency to assume a certain mindset through which we interpret the world. This makes for differences in our styles of leadership and our understanding of values. Mindsets are like glasses through which we see the world and construct our own worldview and the narrative of our lives. Colleagues with a more mature mindset are unwilling to be led by someone with a simple view of the world who is, for instance, fixated on figures. Agility cannot be achieved in a company structure obsessed by controlling. This is why management has become a bottleneck in many organisations.

The biggest challenge of digital transformation is broadening old mindsets,analysingyourself and finding your way to a genuine “we”.

This becomes possible when we cease to be judgmental, abandon our cynicism and become more truthful in our interactions with one another. This development which leads to self-management and meaningful action requires a preparedness on our part to accept and internalise new mindsets. We can then relinquish our old interpretations of what things are and how they should be. It’s a mental process that requires time and patience (See diagram on page 97).

4. Using the potentiality space and ensuring harmonisation

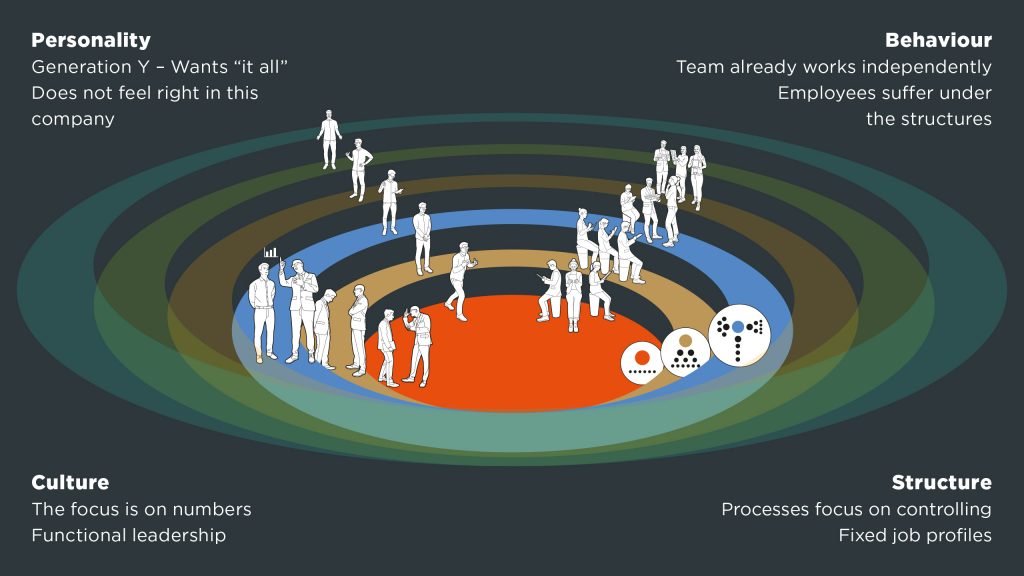

Harmonisation of the values and mindsets of managers and employees determines whether and how the development of all individual employees will succeed, and how capable of development the overall company is. Such harmonisation can be fostered by illuminating four key aspects of the predominant mindsets:

- How developed are the personalities, the mindsets of the employees?

- Which behaviour patterns are now prevalent among the employees?

- Which structures and processes do we use?

- What are the most important beliefs and values enshrined in our corporate culture?

The Generation Y phenomenon has made the differences between customary attitudes and values and the needs of young employees particularly clear. Particularly in large companies, they find the structures and culture far too rigid and unappealing. These no longer correspond to their mindset and the way they view themselves. Many companies still use controlling-oriented processes and inflexible job descriptions that turn people into functional units. This used to make sense from a rationalist functional standpoint. Yet it is distasteful to people who have learnt to shoulder their own responsibility for the work they do. Many companies seek to influence their employees’ behaviour through the introduction of single measures such as design thinking or agile methods that make employees more innovative and open to change. Yet they forget that employees’ behaviour is first produced by adaptation to the company culture and its existing structures.

Consequently, many people remain under their potential not because they don’t want to or can’t improve it, but because there are systemic obstacles put in their way.

The real obstacles frequently lie in rigid structures and a hierarchical understanding of management. The mindset model supports the identification and purposeful development of such differences. The potentiality space should be more or less equally developed on all its levels. Ideally, the culture and its embodied values should be a bit more mature than the employees because then the culture becomes an additional leader and not a demotivating obstacle. At the same time a systemic understanding of management is needed to recognise just where individual employees stand and what kind of management is appropriate for them. Not all employees find it easy to take their own responsibility or to learn self-management. However, if the mindset of management or their level of maturity is the bottleneck, this will block the development of the whole organisation.

A company that purposefully recruits new employees of a more mature mindset with a view to increasing its innovation power would be well advised to be equally clear in communicating this to them. This preempts disappointment on both sides and ensures that the venture can be successful.

When it comes to the harmonisation of the values held by employers and employees, the spotlight is clearly on one thing alone – the development of management personality towards greater emotional competence. As a cultural leader, management has a profound impact on the whole system. Gender equality is also one of the important aspects of the move to a broadened set of competencies and empathic systemic management.

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast, structure eats culture for lunch, mindset eats structure for dinner”

This article in german first appeared in 2019 in Booksprint Vereinbarkeit 4.0, Bertelsmann Stiftung. Forty nine authors shared their thoughts and views on “Compatibility 4.0”. It´s also available as a blogpost in German.